The Cinematic Blueprint

of Political Polarisation

When Joseph Goebbels declared that cinema was one of the most powerful

weapons in the arsenal of the state, he was not being hyperbolic. As Nazi

Germany perfected the art of propaganda, film became more than a medium of

entertainment—it became an instrument of indoctrination. Almost a century

later, the template remains eerily relevant. In democracies and autocracies

alike, propaganda cinema continues to thrive, shaping public opinion, altering

historical memory, and manipulating national consciousness.

The Craft of Conviction

At its core, a propaganda film does not merely present a narrative—it

constructs a moral universe. Villains and heroes are painted in broad,

unambiguous strokes. Complex socio-political realities are reduced to binary

choices: nationalism versus anti-nationalism, civilization versus barbarism, us

versus them. When such simplifications are backed by powerful imagery, emotive

music, and gripping performances, the impact on the psyche of viewers can be

profound.

Propaganda cinema cloaks itself in patriotism and purpose. It portrays

dissenters as traitors, minorities as threats, and ideological opponents as

enemies of the state. The intention is never just storytelling—it is

nation-building, or more aptly, nation-moulding.

Yet, it is important to distinguish between dissent and hate. Not all

political cinema is propaganda. Films like Kissa Kursi Ka (1977) and Aandhi

(1975) questioned power and critiqued the system, but they did so without

vilifying communities or weaponizing religion. They were voices of resistance

in the truest democratic sense—satirical, symbolic, and aimed at the abuse of

authority, not at inciting societal divisions. Unlike modern propaganda films,

these classics did not seek to create an "enemy within." They

questioned rulers, not citizens.

The Indian Context: Beyond Entertainment

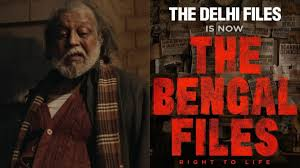

In contrast, the recent surge in politically charged films such as The

Kashmir Files, The Kerala Story, and the upcoming The Delhi Files

marks a troubling evolution. These films do not merely reflect the political

mood—they are part of the machinery shaping it. Wrapped in the language of

"truth-telling" and "bringing hidden histories to light,"

such films often distort facts, cherry-pick incidents, and weaponize trauma.

Now, Vivek Agnihotri, the director of The Kashmir Files, is

working on The Bengal Files, a film purportedly based on political

violence in West Bengal. Given Agnihotri’s established pattern—where history is

viewed through the lens of communal victimhood and ideological warfare—The

Bengal Files appears less like investigative storytelling and more like the

continuation of hate politics through cinema. The project, unveiled amid

political turbulence in Bengal, seems poised to further polarize public opinion

in a state already grappling with deep-rooted tensions. Its objective appears

less about truth and more about reinforcing a national narrative of siege and

division.

Follow the Money: Who’s Funding the Propaganda?

The success of these films isn't accidental—nor is their financing merely

artistic. A closer look reveals an intricate ecosystem where ideology, money,

and political power work hand in hand.

1. Producers with Political Links

Many of these films are backed by producers with visible or tacit ties to

the ruling party.

The Kashmir Files, for example, was co-produced by Zee Studios

and Abhishek Agarwal Arts—the latter run by a Hyderabad-based

businessman known for his proximity to BJP leaders. The Kerala Story was

produced by Vipul Amrutlal Shah, a filmmaker whose public statements

often mirror Hindutva rhetoric.

2. Government Patronage as Indirect Funding

No government official writes a cheque—but support comes in subtler, more

powerful forms:

- Tax exemptions granted by BJP-ruled states,

- Free screenings for students, police, and bureaucrats,

- Public endorsements by top leaders including the Prime Minister,

- And amplification

by the BJP’s digital ecosystem, giving these films the kind of reach

most filmmakers can only dream of.

Such soft backing dramatically reduces costs and guarantees

attention—making it a kind of de facto state subsidy.

3. Shadow Funders and Ideological Venture Capital

A number of relatively unknown production houses have suddenly emerged with

unexplained funding muscle. These are often linked to:

- Real estate and

mining interests,

- Businessmen aligned

with ruling party agendas,

- Or shell companies

connected to media empires sympathetic to the regime.

While direct evidence is scarce due to opaque financial structures,

patterns of political timing and exclusive access to resources strongly suggest

orchestrated support.

4. Ideologically Driven Directors

Directors like Vivek Agnihotri, who calls himself a “cultural

warrior,” are no longer just storytellers—they are missionaries with a camera.

His close appearances with RSS-affiliated organizations and ideological think

tanks like India Foundation suggest that these films are not independent

creations—they are commissioned narratives. The Bengal Files, in this

context, appears not as journalism through art but propaganda through

celluloid.

Cognitive Capture: The Mind as a Battlefield

A critical aspect of propaganda films is their ability to bypass critical

reasoning. Neuroscience suggests that emotionally charged visuals activate the

amygdala—the brain’s fear center—suppressing rational thought and enhancing

memory retention. In other words, when a film shocks or angers us, it leaves a

deeper impression than a news article or policy paper ever could.

This is particularly dangerous in a society where media literacy is low and

cinema remains the most accessible form of mass communication. A citizen who

watches a communal propaganda film may not consciously become prejudiced, but

the seeds of bias are sown. Repetition, emotional manipulation, and social

reinforcement (via WhatsApp forwards, social media memes, or television

debates) water those seeds until they blossom into conviction.

What begins as “just a movie” soon becomes the basis of “I heard

somewhere,” which hardens into “I know this happened.” The leap from perception

to belief is barely noticed.

From Socio-Politics to Geopolitics

The domestic impact of propaganda films is grave, but their geopolitical

implications are equally troubling. When films demonize an entire religion or

community—be it Muslims in India, immigrants in the U.S., or Uyghurs in

China—they don’t just influence internal discourse. They signal to the world a

nation’s ideological trajectory.

India, once proud of its pluralism, now finds itself defending against

charges of Islamophobia, partly because of the global reach of its domestic

narratives. When state-backed or state-endorsed films project a unidimensional

nationalism, it affects bilateral relations, diplomatic equations, and even

trade alliances.

Moreover, authoritarian regimes have long understood the power of cinema in

projecting soft power abroad. Russia, China, and Turkey have invested heavily

in period dramas and nationalist blockbusters that export their worldview

globally. The battle for narrative supremacy has moved beyond battlefields and

boardrooms—it now plays out on Netflix, YouTube, and Prime Video.

The Fragile Viewer: Consent Without Awareness

Perhaps the most insidious feature of propaganda cinema is its subtle

violation of the viewer’s consent. When we watch political speeches or campaign

ads, we do so with a sense of guardedness, aware that persuasion is the intent.

But cinema disarms us. We walk into a theatre seeking entertainment, not

ideology. We let our guard down, suspend disbelief, and allow ourselves to be

swept away.

This is precisely what makes propaganda films so effective: they do not

argue, they hypnotize.

In a healthy democracy, films should provoke thought, not paralyze it. They

should ask questions, not issue verdicts. When cinema begins to echo only one

kind of nationalism, one kind of history, one kind of heroism—it ceases to be

art and becomes artillery.

Conclusion: Between Truth and Trauma

As citizens, we must remain vigilant. Not all films are propaganda, and not

all propaganda films wear the mask of nationalism. Sometimes, the bias is

subtle—a line here, a stereotype there. Sometimes, it is blatant. But in every

case, the effect is cumulative.

We must ask: Who made this film? Who funded it? Why now? Whose version of

history is being told? What is being omitted? And what purpose does it serve?

Cinema has the power to heal, to build bridges, to imagine new futures. But

when wielded irresponsibly, it can also inflame, divide, and destroy. A nation

that treats film as a weapon rather than a mirror will eventually lose sight of

its own reflection.

Author: Siddhartha Shankar Mishra is an Advocate at the

Supreme Court of India. He writes on law, politics, and culture, often

exploring the intersection between power and perception.

No comments:

Post a Comment